This series is a work in progress, including the draft below.

La ubicuidad del dios cristiano es un privilegio europeo impuesto a través de la colonización.

I’m an immigrant and American citizen born in Cusco, Perú, capital of the Inka Empire and later a strategic power center of the Spanish colonial era. While growing up my visual surroundings were contemporary urban and rural sceneries against the monolithic presence of pre-columbian and colonial aesthetics, both of which define Peruvian landscapes. My identity as a person and as an artist is marked by them and my body of work often summons their presence.

Chroniclers that documented the cultural, economic and social takeover of the territory have illustrated the efforts of the Catholic Church to consolidate European power while expanding its own grasp. The papal bulls from the 15th and early 16th centuries known as Patronato Real had determined a lucrative partnership between the Vatican and the Spanish Crown. The Crown acquired the responsibility to promote the conversion of the indigenous of the Americas to Catholicism. The expansion of the Church’s missions afforded an increasing income from the levied taxes and control over tithe income. The Catholic Church operated in the interests of the Spanish Crown from the start, and in so doing it erased many spiritual worlds, with success.

Researching Church involvement in processes of colonization brought to my attention the Vatican’s ethnological museum, Anima Mundi. From 14th century Papal Bulls to the 1925 Pontifical Missionary Exhibition, patterns emerged. Historian Gloria Jane Bell writes of the 1925 Exhibition as correlating with North-American ‘Native’ Boarding Schools, both serving “as part of the settler-colonial project for the eradication of Indigenous life ways,” proclaiming papal authority and Western cultural supremacy. “The inclusion of Indigenous cultural belongings from the Americas bolstered the visual consumption and viewing experience of Catholic citizens through hierarchies of vision that also reinforced a hierarchy of race and the arts established by the organizers.” As with anthropological museums, objects exhibited are uneasy reminders of alternative beliefs and triumphs of colonization.

Serendipitously, an obscure news clip surfaced in my research. In 2019 a young Austrian Catholic priest reenacted a centuries long tradition of religious intolerance during the Synod of Bishops on the Pan-Amazon Region. He threw what he alleged to be Pachamama “idols” into the Tiber River. The statues, identical carved images of a pregnant woman, had been used during the synod‘s events.

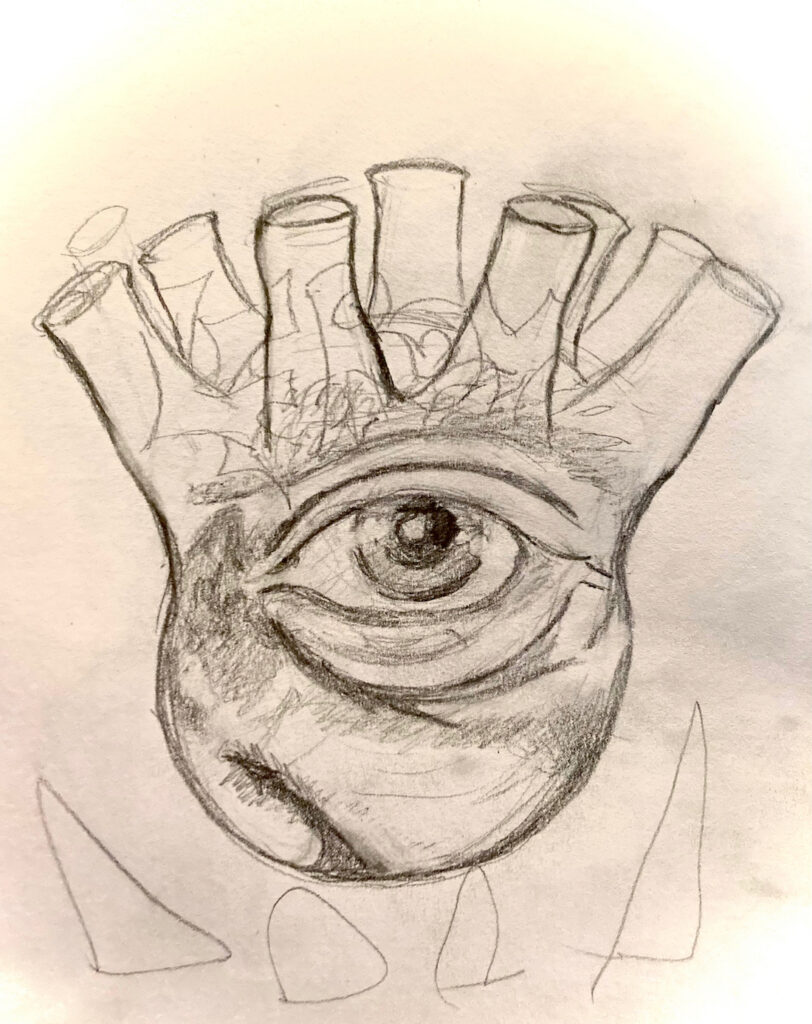

Contemplating the repudiation suffered by the symbolic Pachamamas at the synod, and the Western belief of religious superiority I aspire to inform and affirm the right to exist of such an entity and others through a new project I titled De Las WAK’AS y Las PACHAMAMAS, demanding democratic rights for all beliefs.

Accordingly to Cesar Itier in his essay Huaca, a Misunderstood Andean Concept, there was no concept in Andean languages Quechua or Aymara similar to that of ‘sacred’: something separated from the profane. It brings to mind Marisol de la Cadena’s book Earth Beings where she states the West always understands the “other” through inaccurate translation.

Wak’as, Itier explains, are petrified relics of mythical ancestors, departing from the idea of “partition”. It is the lithic double of a persona who had formed at the time of death. “Only by extension or metonymy, the same term designated or qualified …the …shrine built to accommodate the petrified “soul”; … the mythical ancestors when they lived..” and the little objects, perhaps unfoldings of these entities’ physicality, given away by them “to act as generative prototypes of family wealth”. Pachamama is of course, not idol, but earth. “She” is an inclusive omnipresent entity where plants grow and birds sing, even if suffocated under cement, never loosing the capacity to support life.

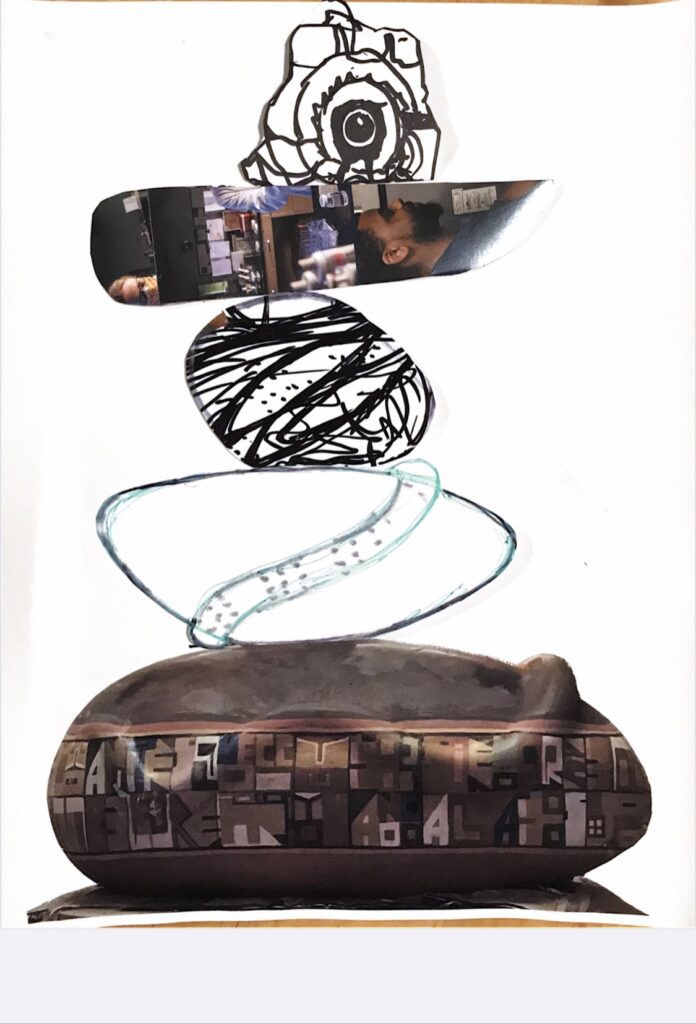

My practice revolves around the consequences of colonization, reclaiming a gaze both synchronous to our time yet rooted in pre-columbian and colonial sensibilities. My series PLUNDER ME BABY was commentary on controversial collections of pre-columbian ceramics in anthropological museums.

The last project CORPUS considered the syncretic survival of ancient entities incorporated within Catholic imagery as metaphors of resistance and negotiation. In this project I depart from anthropomorphic representations. I gather entities to a conceptual foreground, as hypothetical imaginaries of “otherness.” The work acknowledges the pre-colonial surviving entities, respectfully protecting and retaining memory and the opportunity for reinvention, a second chance to re-align historical narratives of decolonization. It is a personal primordial task to understand which is my cultural patrimony as a multi racial and historical hybrid. In whose hands is placed the possibility of continuity? Can I have as a “mestiza”, aesthetic decisions different than Western?

Andean religious, is part of my patrimony and I believe it deserves respect and acknowledgement, and I see it as a personal point of departure with the goal of inserting myself in a historic and aesthetic construct created by people who look like me and are my ancestry. I am interested in researching concepts that can be applied within different cultural landscapes. For example, understanding the philosophical ubiquity of Pachamama. Finding “her/them” in Philadelphia or any city of the world, as well as recognizing spirits of the mountains (Apus), in Perú as well as in the Great Canyon or Yellowstone Park. Researching locations and bringing to the foreground their own entities within the understanding of Andean philosophy.

Indoctrination promotes erasure, becoming a powerful weapon of colonialism. It makes us wonder how societies would have developed if their epistemai had not been so deeply disturbed. How can we build and protect pluriversal worlds? How can we materialize diversity beyond abstract academic verbiage? To me, a strategy is bringing to the foreground cultural inheritances without fear, tackling in personal taste, questioning aesthetic hierarchies, allowing ourselves to be “the other” fully.